Up to 80% of plastics lose quality when melted, making them hard to recycle.

Recently, our team has come across a key problem in the way we recycle products - or at least try to.

When it comes to plastic pollution, people immediately think of recycling. But plastic pollution has a lot more involved than recycling. To set the foundation here, plastic pollution is the problem of dealing with our plastic waste in a way that prevents it from ending up haphazardly in the environment.

There are different ways to solve this problem, which we call different ways of waste management. Recycling is one method of waste management, amongst others like incineration or disposal in landfills/dumps.

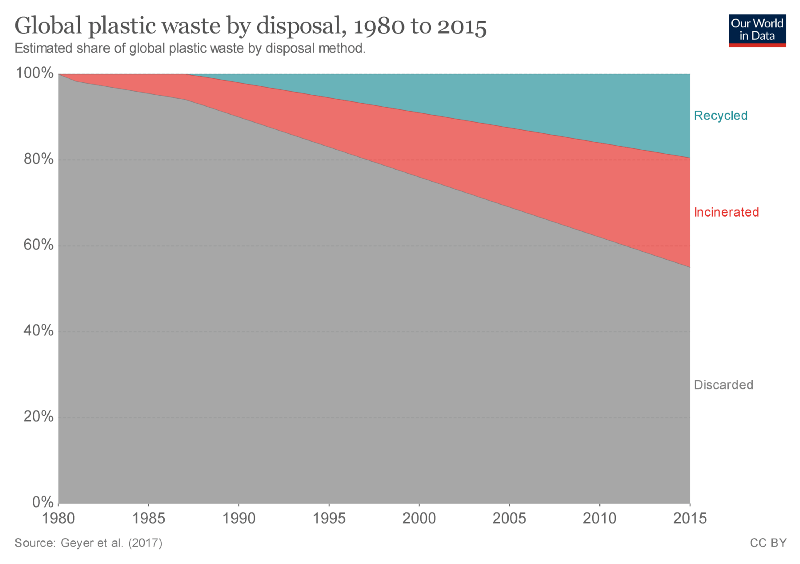

In 2015, the breakdown of the type of waste management used to get rid of plastics around the world looked like this:

To be specific, recycling dealt with 19.5% of plastic waste in 2015. This varies a lot from country to country. For instance, under 10% of municipal plastic waste was recycled in the US in 2019 (Source). In comparison, 38% of plastics in Germany were recycled in 2018 (Source).

When plastics aren't recycled, they're usually sent to a landfill/dump or incinerated - although there are other waste management approaches being developed.

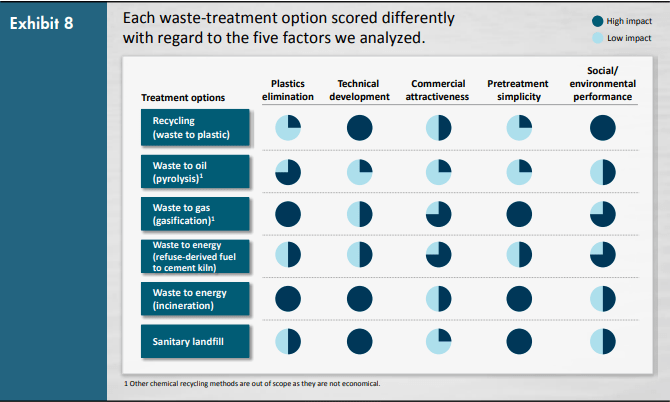

The issue is that these other methods of waste management are more harmful for the environment. Here are some waste management methods compared in general (they include more than just incineration, landfills, and recycling)

So obviously there are ups and downs to all the different waste management methods. But in terms of helping create an environmental impact, the best way to move forward is by increasing recycling.

By reaching this conclusion, we wanted to figure out which factors were limiting an increase in recycling rates. Just from the above graphic, you can see that one of them is commercial attractiveness.

When it comes to commercial attractiveness in the recycling industry, the core issue is simple. To paraphrase a conversation I had with Shaun Frankson, CTO of Plastic Bank: you have to figure out how to get the maximum possible economic output from the plastic input.

In this sense, it's all about addressing the challenges that come about from turning the plastic that you receive in a recycling facility into output (called feedstock) that you can process into plastic products.

Now, trust me - there are a LOT of challenges. From all the difficulties sorting plastics by type (so you can sell different types to specific manufacturers) to dealing with contamination from other materials (ex. organic material from food containers) to dealing with the competition of just making new plastic products instead of ones from recycled plastics based on how cheap oil prices are…

That being said, there was one key issue that our team found to be a promising lead. When it comes to recycling plastics by type, according to Ocean Conservancy - 80% of plastic waste has low residual value (Source)

What does that mean? Basically, when you try to recycle the plastic material into a new application, the material loses quality. Ie. instead of the material getting REcycled, it's being DOWNcycled. Since the majority of plastic waste is like this, most plastic can only be recycled once or twice before it can't be processed anymore.

Our team found this very surprising. What about recycling makes 80% of plastics not have much value? It has to do with one specific part of the recycling process: melting the plastic down to reshape it into new products.

This melting is the reason why plastics have to be sorted in the first place - different plastic types (or polymers) have different melting points (Source). So they can't all be processed the same way. Another issue when you're melting plastics comes about with melting specific plastic types.

One type of plastics called thermoplastics are plastics that harden as you heat them. Once they're moulded with heat into their final shape, they can't be remelted anymore (Source). This means they can't be recycled into new products.

Also, with most plastic types, when you melt them to remould them into some new application - their structure changes at the molecular level. Many plastics are made up of polymers (long chains of atoms) that get shorter and shorter each time you melt them for recycling (Source). This is what makes those 80% of plastics have low residual value - they lose quality every time we try to recycle them.

This made us wonder… why not just STOP melting the plastics? For instance, why is it that we can't recycle plastics by shredding them into smaller pieces and compressing them into solids? This would seem to get around the whole issue of 80% of low-value plastics not being able to be recycled.

This approach is actually being used by some social impact nonprofits and startups - although it's not the norm. For instance, Planet Love Life creates jewelry by tearing up pieces of recycled fishing nets.

Additionally, based on conversations we've had with Charles Rolsky, CSO of Plastic Oceans and Professor Martin Medina at the United Nations University - we think it's promising to explore further methods of repurposing low residual value plastics for new applications.

That being said, we've also seen conflicting evidence about the proportion of plastics that actually are low-value. From my conversation with Shaun Frankson, CTO of PlasticBank - he definitively told me that PlasticBank didn't have a proportion of plastic that high which wasn't able to be recycled. We're reaching out to hear more about their innovations to be the outlier in the industry!

As a whole though, our team is currently moving forward with this idea to explore new ways to repurpose plastic. There are many viable alternatives - from creating plastic construction materials to selling plastic bracelets. But many of them have their problems. That's a topic for another post though, so we'll keep you updated on our findings!

Further Reading: