Often times, we talk about the environmental problems caused by plastic pollution while ignoring its impacts on humans.

While many of us might be familiar with the environmental impacts of plastic pollution, there’s still another part of the problem that needs to be addressed: its effects on humans. The negative consequences of this problem are most clearly seen in developing countries.

There is a huge disparity between the situation in developed and developing countries. Let’s look at an example: for every 30 seconds in the UK, there is enough plastic waste generated to fill 2 double-decker buses. On the other hand, in developing countries, there’s enough plastic waste generated to fill 30 double-decker buses (Source).

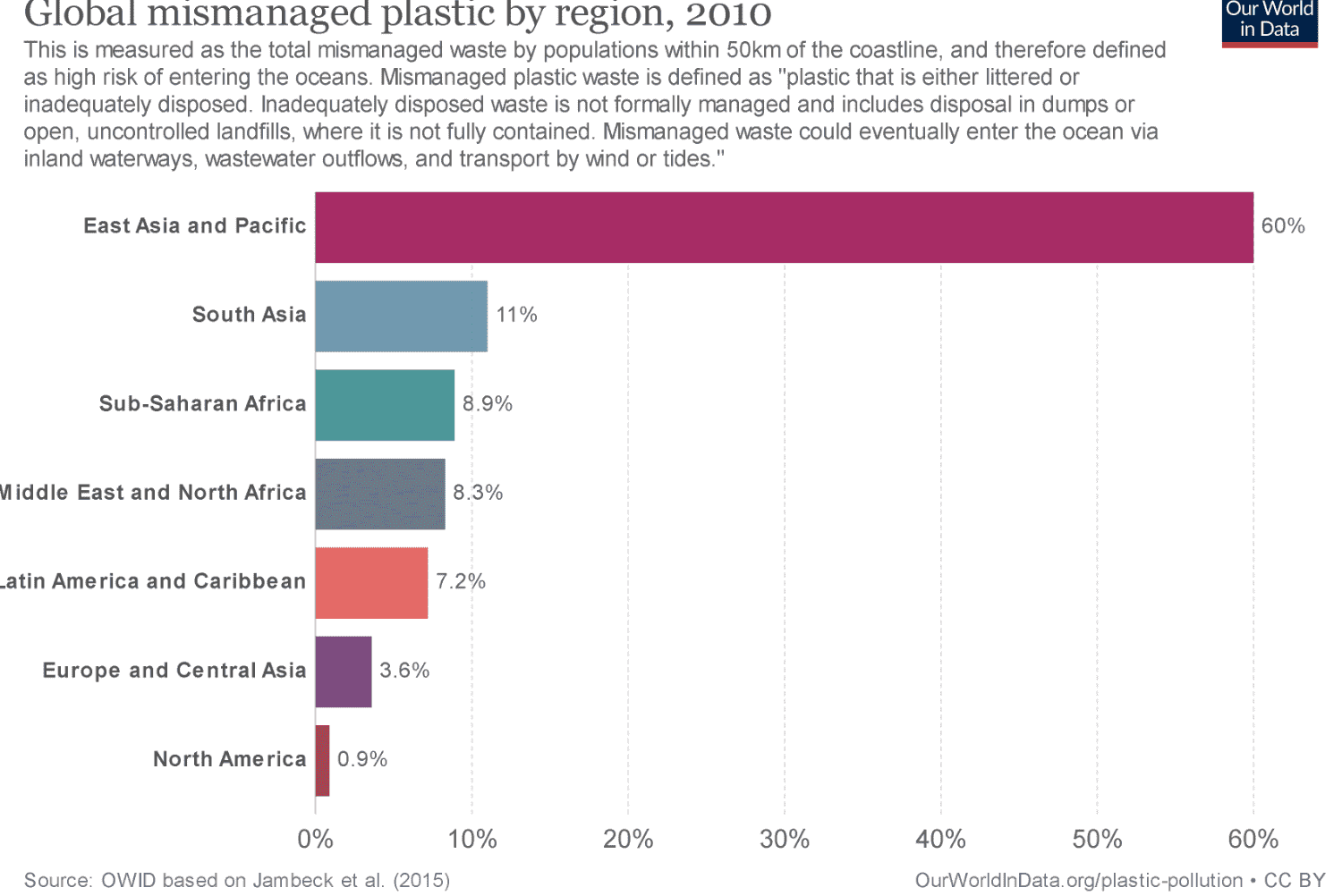

As it turns out, there is a strong correlation between poverty and plastic pollution. In fact, over 70% of plastic waste that enters the oceans comes from developing countries in Asia (Source).

Clearly, there’s an environmental problem here. But, if we focus in more on the day-to-day reality in these developing countries, another problem starts to become apparent. In poorer communities, plastic acts as both a valuable material that is the basis for many people’s livelihoods AND a material that leads to many dangerous side-effects like health hazards (Source).

For instance, plastic packaging (especially for multilayered sachets) is used by many low-income families to obtain items such as toothpaste, coffee, or shampoo every month. While those in developed countries might have the luxury of choice when it comes to what products we can use, these families don’t have enough disposable income to buy larger products. Thus, the producers/consumers buying and selling these plastic products benefit from plastics when they can’t use other materials (Souce).

Yet, these benefits fade away as the plastic products come to the end of their use. Many developing countries lack proper waste management facilities, meaning a large portion of their plastics is disposed of in open landfills after being used. And, unfortunately, this is what’s been causing the brunt of the problems for people’s livelihoods. Between 400,000 and 1 million people every year are dying from illnesses and diseases caused by living near plastic pollution (Source). For context, that’s the death of one person every 30 seconds.

What are the specific problems involved?

These problems mainly affect two groups: consumers and waste pickers.

For consumers, the problems from plastic pollution come from the same categories in developed and developing countries, just to different extents. For instance, we know that some plastics can create negative health impacts when found in consumer products — like BPA that might be ingested through food and beverage containers (Source).

But for many other plastics and petrochemicals, there is a lack of data to understand the complete health impacts they have. For instance, we know that microplastics are prevalent in our food, air, and oceans and can enter the human body by ingestion and inhalation (Source). Yet, it is unclear how that affects humans (or several other species of animals).

Still, we could hypothesise that consumers in developing countries might face a greater potential for danger if there are health risks associated with plastics. This might occur due to less developed healthcare infrastructure, less stringent environmental regulations, etc.

Then, it’s important to focus on the group we do know is harmed by plastics more precisely: waste pickers. There are tens of millions of waste pickers (mostly in developing countries) that make a living from sorting through garbage (often from streetside bins, local homes/businesses, or open dumps) (Source). They are often impoverished and rely on this occupation to earn a basic income. But waste management systems also rely on them, as 15 to 20% of waste is collected by waste pickers globally (Source).

The first challenge they face from this livelihood is that mismanaged waste is capable of spreading diseases in a variety of different ways, even if those diseases are preventable. The illnesses can spread through interactions with waste from floods caused by blocked waterways or through pollutants that are released when waste is burned, for example.

Also, waste pickers have to manually interact with waste every day. This creates risks of exposure to biohazardous, rotting, toxic, allergenic, sharp, or otherwise dangerous materials (especially for waste pickers in open dumps). One study found many waste pickers had unnaturally high rates of health problems including back pain, cuts, malnutrition, bites from stray animals, eye infections, poor gut health, diarrhoea, and skin diseases (Source).

CLEARLY, sorting through plastic waste has health problems for these waste pickers, but that’s not all. Many (but not all) waste pickers face safety hazards from working in open dumps that are sometimes prone to landslides, fires, or other accidents (Source). In Ethiopia, for example, over 115 people died from a landslide in a landfill (Source). And with the ongoing pandemic, waste pickers have been working in conditions where they’re more prone to being exposed to COVID-19, while also facing financial insecurity (Source).

Finally, there are also problems that affect both these groups. For one, incineration facilities in developing countries often pose a threat in causing air pollution due to how close these sites are located to where people are living (Source). This is an important issue due to the growing number of incinerators being developed in Asia, sometimes with inadequate environmental standards (Source).

What to Do About This?

When it comes to problems such as exposure to petrochemicals that are known to be toxic (ex. BPA), there have been regulatory/commercial efforts to phase out the use of BPA in products (which can then be marketed as ‘BPA-Free’). The issue is that sometimes, BPA has been substituted with chemically-similar alternatives that still pose health risks (Source). That said, this issue is drawing attention and invoking progress to be made.

What’s more dangerous is exposure to petrochemicals whose negative health effects are not known (ex. microplastics). More toxicology research is needed to understand the effects of these plastics on human health, but only a few nonprofits are supporting these initiatives (Source). More funding/attention is needed for this research, especially to study groups like waste pickers who are most exposed to these petrochemicals.

Next, the occupational safety hazards faced by waste pickers also need to be addressed. Here, we see solutions being led predominantly by nonprofits and businesses instead of governments, as there is often a stigma associated with waste pickers that cause them to be seen as problems in the overall waste management sector in developing countries (ex. picking garbage from formal street bins, etc.) (Source). This makes governments less likely to enact legislation to improve waste pickers’ occupations.

In terms of other solutions, common ones involve organising waste pickers into larger organisations so that they can operate at larger scales (ex. collecting waste for larger companies willing to pay more). The most scalable way this has been done in developing countries is from a company called Plastic Bank.

They pay waste pickers to collect recyclable materials for them. The collected waste is then sold to large plastic producers (like Henkel) as Social Plastic (plastic that is recycled, but also helps informal waste pickers earn a living) at a premium price. This lets Plastic Bank then pay higher wages to waste pickers and fund initiatives to help their local communities (ex. financial literacy programs).

We're celebrating 7 years!#GreinerPackaging has helped to collect over 176,000 kg of #oceanboundplastic - that's 8.8 million plastic bottles!

— Plastic Bank (@PlasticBank) June 7, 2020

Thank you to our collectors, partners, and employees!

Go Plastic Positive by visiting https://t.co/0JryO6xco3 pic.twitter.com/3Dus8tVGLb

By providing better and more reliable incentives for waste pickers in an otherwise unpredictable industry, Plastic Bank hopes to continue increasing the collection of recyclable plastics in developing countries. Also, their waste collectors often find materials from streets or houses instead of open dumps, making their jobs safer. As of right now, they’ve been able to collect over 11.3 million kilograms of plastic with 19,000 waste pickers in countries like Haiti, Indonesia, the Philippines, etc. (Plastic Bank).

In all, there are several aspects of the plastic pollution problem that affect not just the environment, but also humans. Whether it be consumers being exposed to potentially dangerous chemicals or informal waste pickers in developing countries facing hazardous work conditions, more work and attention is needed for these issues. But as more and more promising work is done on this issue, a future where both the environmental and human problems with plastic pollution are fixed is in sight!

Further Reading: