As more and more companies have been switching to plastic, the question remains: are plastic alternatives really worth it?

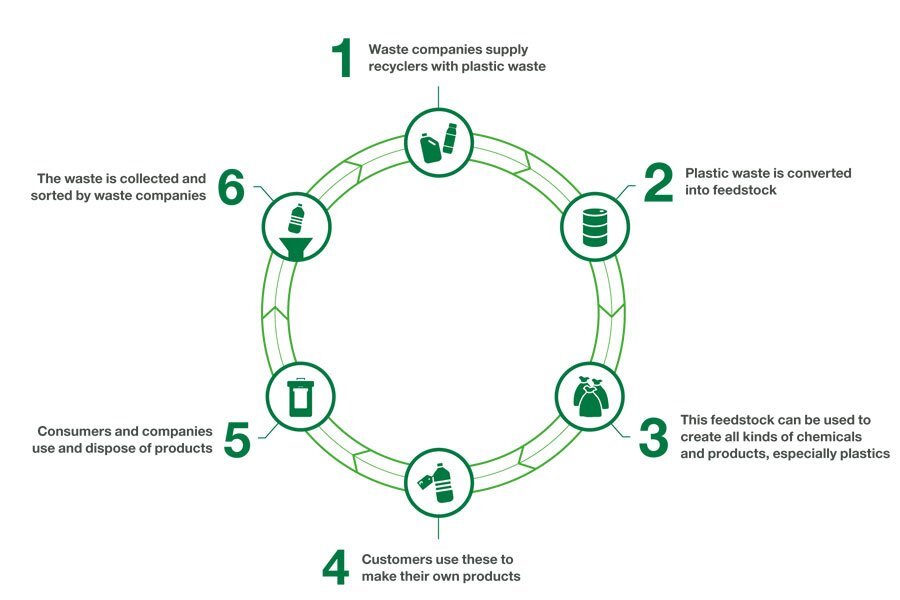

With the hunt for a solution to plastic pollution underway, many corporations have been turning to a newer technology that might help us achieve the goal of creating a circular economy. As one of the latest fads for many corporations, chemical recycling seemed to be a promising tool that could help us improve flaws within the current mechanical recycling systems we have in place. Yes, seemed. Turns out, there’s still quite a bit more that has to be done if we want to adopt chemical recycling on a wider scale - but that doesn’t mean it’s impossible.

Before we discuss some of the downsides of this technology, what exactly is chemical recycling? Simply put, chemical recycling is the process where polymers are chemically reduced into monomers, allowing them to be processed later and used to create plastic products. There are three main types of chemical recycling: solvent-based purification, chemical depolymerisation and thermal depolymerisation. In this article, I’ll be focusing on the first two types since thermal depolymerisation is generally used for plastic to fuel (and you can refer to our article on waste management for more information on that!).

Solvent-based purification

In solvent-based purification, the plastic is immersed in a solvent that allows it to dissolve and revert back to its polymer stage. This solvent is specially chosen so that other impurities such as additives or pigments can be removed through filtration or phase extraction. While I won’t go too much into detail regarding the chemistry of how it all works, what you need to know is that the output is a polymer with sufficient purity – it can be remade into high-quality plastics since all the additives, colourants and contaminants were removed.

But here’s the catch: solvent-based purification can only deal with homogeneous flows of plastic. That means we’ll need an improved sorting system and large amounts of these sorted plastic if we want to implement this on a large scale. Zero Waste Europe’s report sums up the problem well: “The infrastructure and transport costs are also challenging: plastics are lightweight but production volumes need to be high”. According to them, we’ll need high capacity plants – at least about 10-20 kilotons – to make the investment pay off (and that itself is an expensive endeavour).

Even if corporations could afford these chemical recycling plants, how will we ensure that the input to these plants remain homogeneous? Our current recycling systems are notorious for poorly sorting plastics. Plastic contamination, both accidental and purposeful, are issues that have existed for many years now - it seems as though we’ll have to solve this problem first before we can fully switch to solvent-based purification.

That’s not all though. Polymers need to be processed again to create the new plastic object, meaning polymer length will be shortened anyways, meaning the plastics will be of poorer quality compared to virgin plastic. Then there’s also the issue of how the purity of the output polymer can vary according to the input – there’s always a risk of finding residual contaminants and traces of the solvent.

Chemical depolymerisation

Chemical depolymerisation is essentially the opposite of polymerisation. It’s a similar concept to solvent-based purification in the sense that polymers are broken down into monomers, however this technique is mainly used on polymers formed via polycondensation since the activated bonds can be easily broken. Thus, after the purification steps remove colourants and contaminants, the pure monomer is obtained (or small polymer chains called dimers or oligomers). The resulting output must be polymerised again to form a new plastic product and the length of the polymer chain is not a problem – it can essentially be recycled forever!

One of the biggest criticisms of chemical depolymerisation is the amount of energy required for this process. In order for the polymers to be broken down, you’ll need heat and sometimes a catalyst. The amount of heat needed depends on the input material – multilayer materials need more energy, for example – and there’s a high chance that the process involves the creation of potentially hazardous byproducts.

Also, just like solvent-based purification, a very strict upstream sorting system is required due to the mandatory homogeneous input (and we know that our current recycling sorting systems are not well equipped for these demands).

Finally, there’s the issue of price differentiation. Right now, chemically recycled polymers are still more expensive than virgin polymers. We’ll need to find enough sorted homogeneous plastic waste, infrastructure, and transport and we’ll need market intervention of some sort if we want this to be feasible according to Zero Waste Europe’s report.

So yes, it seems as though we still have a long way to go before either of these technologies become viable for wide-scale use. The truth is, not enough information is currently available regarding the environmental impacts of chemical recycling. What if this process has even worse side effects when compared to our current mechanical recycling systems?

As GreenPeace stated in their report, “Focusing on these new technologies could delay innovation into responsible solutions… while recycling has a limited but important role to play in the short-term, to solve the plastic pollution crisis, we need to create less single-use plastic in the first place.”

Further Reading: